State-Sponsored Lethargy

State-Sponsored Lethargy

State-Sponsored Lethargy

Progress is ratelimited by defective policymaking

Progress is ratelimited by defective policymaking

Progress is ratelimited by defective policymaking

State sponsored lethargy is a structural emergency: American governance has calcified under the bloat of good intentions. In 1900, the federal government spent less than 3% of GDP. Except for the post office, an ordinary citizen could live an entire lifetime without a single direct interaction with the federal government.

Today, 2.9 million federal civilian employees – a population exceeding those of 15 states – administer a budget that consumes 24% of US GDP, yet falls short of the social progress it ostensibly buys. The Department of Veteran Affairs, one of the largest federal health systems, allowed veterans in Phoenix to wait months for basic health appointments while falsifying internal records; Congress pours over $40 billion annually into drug enforcement while the Controlled Substance Act remains frozen in 1970s science; mental health parity laws from 2008 struggle with inconsistent enforcement and oversight between the HHS, DOL, and Treasury. The U.S. has built a bureaucracy capable of spending at scale but incapable of translating that spending into capacity that modern problems demand.

“Our government in Washington now is a horrible bureaucratic mess. It is disorganized, wasteful, and unresponsive … we must give the American people a government that is efficient, economical, purposeful, and manageable."

– Jimmy Carter, 1976.

This has been a known problem for decades. Why, then, has this crisis only worsened?

Bias for bloat

The Courtyards Institute holds that the regrettable decisions that led to our current state of lethargy are a consequence of defective policymaking. The process of Identifying a Problem → Proposing a Solution creates a ratchet effect: it seemingly always requires more funding, more personnel, or more regulation accumulating over time. Incentives on K Street are lamentably misaligned: actors are paid or lauded for maximizing the deployment of taxpayer dollars. This ‘bias for action’ has twisted noble goals into waste of epic proportion.

This predicament is unique to policy. Most other domains face real constraints: in sectors ranging from finance to fishing, to transportation and technology, there is simply no equivalent where unchecked inefficiency is so rewarded.

In fact, the exact opposite can be observed. Constraints of scarcity can lead to incredibly effective decisions, lack of resources notwithstanding. Examples include entrepreneurship, warfare, and the arts.

Constraints work

Startups are famously scrappy. It is this environment of extreme capital starvation that leads to the greatest innovations. Integrated circuits were first commercialized at Fairchild Semiconductor and refined at Intel, not Bell Labs. Reusable rockets were relegated to the realms science fiction until SpaceX entered the fray. When Whatsapp was acquired by Facebook in 2014, it was handling the communication of 450M users with only 32 engineers. The Whatsapp team couldn’t afford to throw bodies at problems, and ended up writing ingenious, scalable, and automated code that larger bureaucracies failed to envision.

Entrepreneurship is not the exception. Military history demonstrates that a smaller, resource-constrained force is often far more strategically agile than a wealthy, bloated superpower. When the Soviets invaded Finland in the 1939 Winter War, the Finns were outsupplied, outgunned, and out-bureaucracied. With only 32 tanks to the USSR’s 6,500, adaptation became necessary for survival. In the face of need, the Finns invented an entirely novel way of war, creating “Motti” tactics that broke down invading forces into more easily defeatable pockets. In an example closer to home, the US military lost much dynamism after the anticompetitive 1990s corporate consolidation of contractors from 51 companies to 5. For example, under the urgent and constrained conditions of World War Two, the legendary P-51 Mustang was designed and flown in just 102 days. In contrast, the development cycle of the F-35 was over 20 years: more than the entire duration of WWI, WWII, and the Korean War combined. Even then, there are numerous criticisms of the stealth jet. Policy with good intentions (de-arming after the Cold War) led to bureaucracy and bad outcomes.

Constraints lead to masterpieces of art, too. Consider the structure of a Haiku. The poet is granted a meager allowance of just 17 syllables. This severe restriction does not stifle expression; instead, it forces the writer to strip away the trivial and focus entirely on the essential. Today, haikus are an immensely popular and successful style of poetry. Contrastingly, in cinema, Disney’s The Lone Ranger is a prime example of bureaucratic excess. With a staggering budget of $225 million, the production drowned in its own resources. It lost the studio over $190 million. On the other hand is Hollywood's most profitable film, Paranormal Activity. The director had a production budget of only $15,000. He could not afford CGI, A-list actors, or multiple locations, and was instead forced to greatly innovate - and ultimately popularize - the found footage genre that major studios overlooked. Paranormal Activity became a once-in-a-generation film with a box office gross of $193 million, yielding a return on investment of over 12,800%.

It is evident that constraints make diamonds of coal, and we believe that policy has been missing this alchemy for too long.

Our view

The Courtyards Institute’s unique perspective is that:

1. Policy must match the real-world constraints of other industries with its own, self-imposed ones.

2. A think tank composed of undergraduate and graduate students - and therefore with no financial incentive - is best able to impose these constraints upon itself.

Our donors do not care for high government spending, nor flashy bureaucratic appendages. Our singular goal is to deliver the most impactful policies with the least amount of bureaucracy. We do this by developing policy that requires the least quantity of funding and leads to the least amount of red-tape. There is a Pareto frontier between impact and bureaucracy - all of our work intentionally dedicates substantial study and resources into finding it.

We hope that policymakers find the materials we produce useful, and join us in advancing towards the national interest.

State sponsored lethargy is a structural emergency: American governance has calcified under the bloat of good intentions. In 1900, the federal government spent less than 3% of GDP. Except for the post office, an ordinary citizen could live an entire lifetime without a single direct interaction with the federal government.

Today, 2.9 million federal civilian employees – a population exceeding those of 15 states – administer a budget that consumes 24% of US GDP, yet falls short of the social progress it ostensibly buys. The Department of Veteran Affairs, one of the largest federal health systems, allowed veterans in Phoenix to wait months for basic health appointments while falsifying internal records; Congress pours over $40 billion annually into drug enforcement while the Controlled Substance Act remains frozen in 1970s science; mental health parity laws from 2008 struggle with inconsistent enforcement and oversight between the HHS, DOL, and Treasury. The U.S. has built a bureaucracy capable of spending at scale but incapable of translating that spending into capacity that modern problems demand.

“Our government in Washington now is a horrible bureaucratic mess. It is disorganized, wasteful, and unresponsive … we must give the American people a government that is efficient, economical, purposeful, and manageable."

– Jimmy Carter, 1976.

This has been a known problem for decades. Why, then, has this crisis only worsened?

Bias for bloat

The Courtyards Institute holds that the regrettable decisions that led to our current state of lethargy are a consequence of defective policymaking. The process of Identifying a Problem → Proposing a Solution creates a ratchet effect: it seemingly always requires more funding, more personnel, or more regulation accumulating over time. Incentives on K Street are lamentably misaligned: actors are paid or lauded for maximizing the deployment of taxpayer dollars. This ‘bias for action’ has twisted noble goals into waste of epic proportion.

This predicament is unique to policy. Most other domains face real constraints: in sectors ranging from finance to fishing, to transportation and technology, there is simply no equivalent where unchecked inefficiency is so rewarded.

In fact, the exact opposite can be observed. Constraints of scarcity can lead to incredibly effective decisions, lack of resources notwithstanding. Examples include entrepreneurship, warfare, and the arts.

Constraints work

Startups are famously scrappy. It is this environment of extreme capital starvation that leads to the greatest innovations. Integrated circuits were first commercialized at Fairchild Semiconductor and refined at Intel, not Bell Labs. Reusable rockets were relegated to the realms science fiction until SpaceX entered the fray. When Whatsapp was acquired by Facebook in 2014, it was handling the communication of 450M users with only 32 engineers. The Whatsapp team couldn’t afford to throw bodies at problems, and ended up writing ingenious, scalable, and automated code that larger bureaucracies failed to envision.

Entrepreneurship is not the exception. Military history demonstrates that a smaller, resource-constrained force is often far more strategically agile than a wealthy, bloated superpower. When the Soviets invaded Finland in the 1939 Winter War, the Finns were outsupplied, outgunned, and out-bureaucracied. With only 32 tanks to the USSR’s 6,500, adaptation became necessary for survival. In the face of need, the Finns invented an entirely novel way of war, creating “Motti” tactics that broke down invading forces into more easily defeatable pockets. In an example closer to home, the US military lost much dynamism after the anticompetitive 1990s corporate consolidation of contractors from 51 companies to 5. For example, under the urgent and constrained conditions of World War Two, the legendary P-51 Mustang was designed and flown in just 102 days. In contrast, the development cycle of the F-35 was over 20 years: more than the entire duration of WWI, WWII, and the Korean War combined. Even then, there are numerous criticisms of the stealth jet. Policy with good intentions (de-arming after the Cold War) led to bureaucracy and bad outcomes.

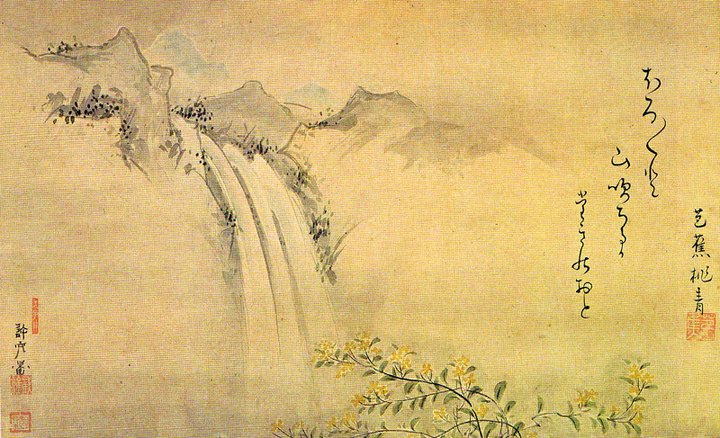

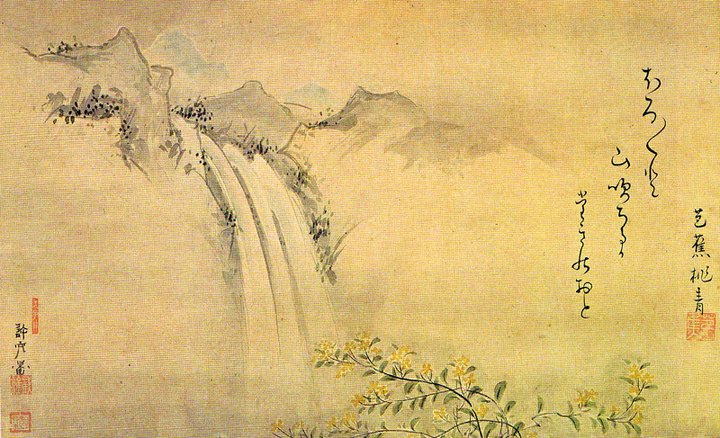

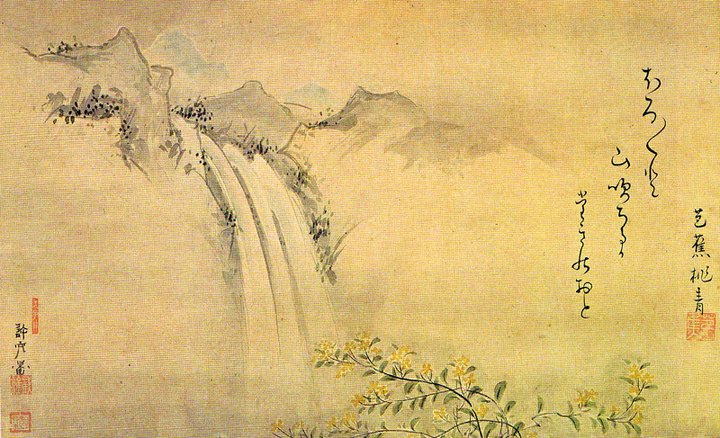

Constraints lead to masterpieces of art, too. Consider the structure of a Haiku. The poet is granted a meager allowance of just 17 syllables. This severe restriction does not stifle expression; instead, it forces the writer to strip away the trivial and focus entirely on the essential. Today, haikus are an immensely popular and successful style of poetry. Contrastingly, in cinema, Disney’s The Lone Ranger is a prime example of bureaucratic excess. With a staggering budget of $225 million, the production drowned in its own resources. It lost the studio over $190 million. Contrast this with Hollywood's most profitable film, Paranormal Activity. The director had a production budget of only $15,000. He could not afford CGI, A-list actors, or multiple locations, and was instead forced to greatly innovate - and ultimately popularize - the found footage genre that major studios overlooked. Paranormal Activity became a once-in-a-generation film with a box office gross of $193 million, yielding a return on investment of over 12,800%.

It is evident that constraints make diamonds of coal, and we believe that policy has been missing this alchemy for too long.

Our view

The Courtyards Institute’s unique perspective is that:

1. Policy must match the real-world constraints of other industries with its own, self-imposed ones.

2. A think tank composed of undergraduate and graduate students - and therefore with no financial incentive - is best able to impose these constraints upon itself.

Our donors do not care for high government spending, nor flashy bureaucratic appendages. Our singular goal is to deliver the most impactful policies with the least amount of bureaucracy. We do this by developing policy that requires the least quantity of funding and leads to the least amount of red-tape. There is a Pareto frontier between impact and bureaucracy - all of our work intentionally dedicates substantial study and resources into finding it.

We hope that policymakers find the materials we produce useful, and join us in advancing towards the national interest.

Martin Johnson Heade, Approaching Thunder Storm, 1859

Matsuo Basho, Horo Horo To, 1693

Carl Bersch, Lincoln Borne By Loving Hands, 1895